Conceptual blending

Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner‘s The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities gives us a fascinating look at the way the human mind weaves a world out of seemingly disparate elements — in a very similar manner to that in which the creative mind weaves an aha! out of seemingly disparate ideas. The book deals with the formation of perceptions as well as ideas, but it was a specifically conceptual blend that intrigued me the other day.

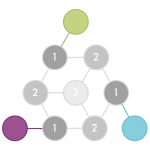

First, they note that when we use expressions like “I had reached the boiling point. I was fuming. He exploded.” we are making a metaphorical mapping in which “a heated container maps to an angry individual, heat maps to anger, smoke and steam (signs of heat) map to signs of anger, explosion maps to uncontrolled rage.” Then they add in the “folk theory of physiological effects of anger” including ” increased body heat, blood pressure, agitation, redness of face” – and thus we have a threefold scheme, in which physiology, emotions and the physics of heat are intricately cross-correlated, so that we can say without much thought “He was so mad I could see smoke coming out of his ears”.

Here Fauconnier and Turner describe the mechanics of this remarkable conceptual blending process – which can yield such a seemingly unremarkable phrase:

In addition to the metaphoric mapping between Heat and Emotions and the vital-relation connection between Emotions and Body, there is a third partial mapping between Heat and Body. In this mapping, steam as vapor that comes from a container connects to perspiration as liquid that comes from a container, the heat of a physical object connects to body heat, and the shaking of the container connects to the body’s trembling.

The three partial mappings set the stage for a conventional multiple blend in which the counterparts in the inputs are fused, yielding, for example, a single element that is heat, anger, and body heat and a different single element that is exploding, reaching extreme anger, and beginning to shake. Once we have this blend, we can run it to develop further emergent structure and we can recruit other information to the inputs to facilitate its development.

What interests me here is the phrase:

the inputs are fused, yielding, for example, a single element that is heat, anger, and body heat

and what it reminds me of is CS Lewis writing in The Allegory of Love:

It must always be remembered … that the various senses we take out of an ancient word by analysis existed in it as a unity.

Thus the King James Version of the Bible, John 3.8, reads:

The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit.

In the Greek, the word here translated wind is pneuma, and the sentence accordingly means “the pneuma blows where it wills, and you hear its sound but can’t tell where it comes from or is going: and so it is with all those born of pneuma“…

Recalling Lewis’ remark about the “various senses we take out of an ancient word”, this in turn means simultaneously and without separation:

the wind blows where it wills, and you hear its sound but can’t tell where it comes from or is going: and so it is with all those born of wind…

the breath blows where it wills, and you hear its sound but can’t tell where it comes from or is going: and so it is with all those born of breath…

and:

spirit blows where it wills, and you hear its sound but can’t tell where it comes from or is going: and so it is with all those born of spirit…

Take this a step further, realize that spirit can be defined as what inspires us, and we have:

inspiration blows where it wills, and you hear its sound but can’t tell where it comes from or is going: and so it is with all those born of inspiration…

Four meanings, all making good sense, and all present simultaneously and inseparably in the one gospel phrase…

Now consider that Fauconnier and Turner are speaking of how “three partial mappings set the stage for a conventional multiple blend in which the counterparts in the inputs are fused, yielding, for example, a single element that is heat, anger, and body heat” and compare it with Lewis’ “unity” from which we take out “the various senses” by “analysis”, as applied to the “ancient word” pneuma, with its meaning encompassing wind, breath, spirit… inspiration.

Are wind, breath and spirit or inspiration in fact three “primitives” that conceptual mapping in ancient Greek thought has brought together? What do we gain, and what do we lose if we view them this way?

And what do we lose, what do we gain if we view them as a single rich concept, now reduced to three or four separate — and separately less complexly interesting — ideas?