This post is a web translation of my presentation to the National Digital Forum, Wellington, NZ, on 20 November 2012. (Video recording is here.)

Hello, people. Thank you for having me on this land and at this forum. I’m utterly thrilled to be here – among you all – to talk about this project.

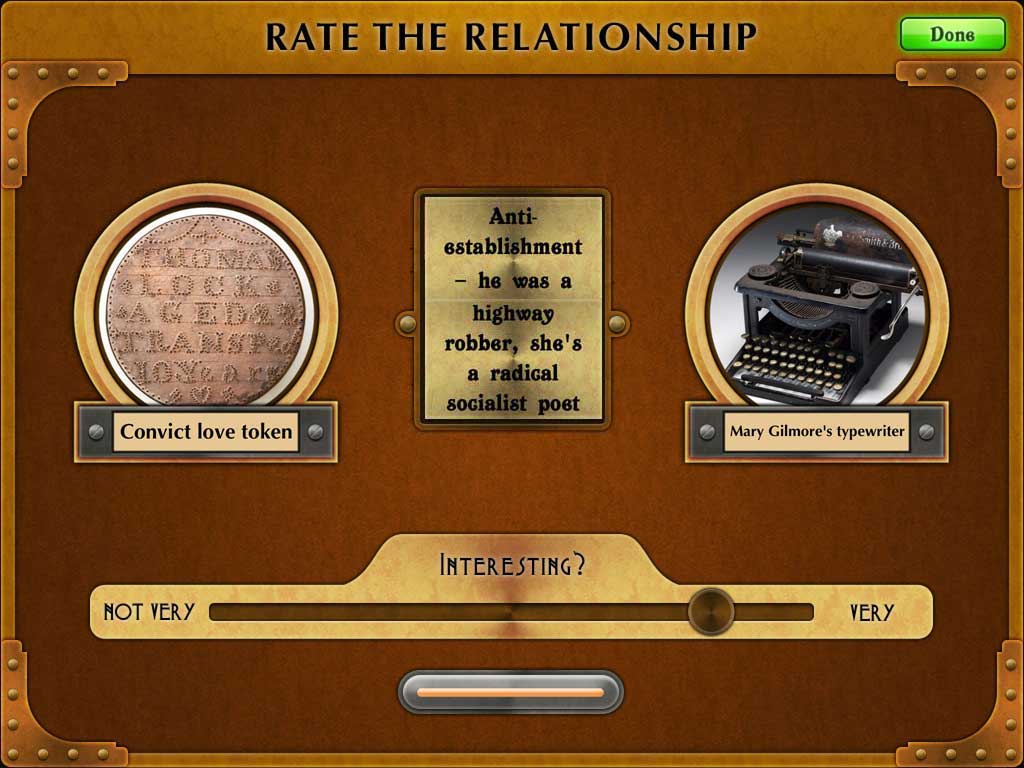

In its first form, Sembl is an iPad game, called The Museum Game, at the National Museum of Australia. We’ve just released it in beta as a program for visiting groups.

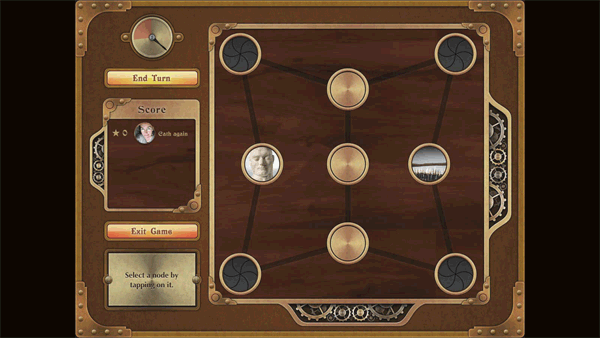

This video is a good way to explain how the game works. (It’s a DIY first attempt, so please look past the production quality and focus on the content.)

Feedback

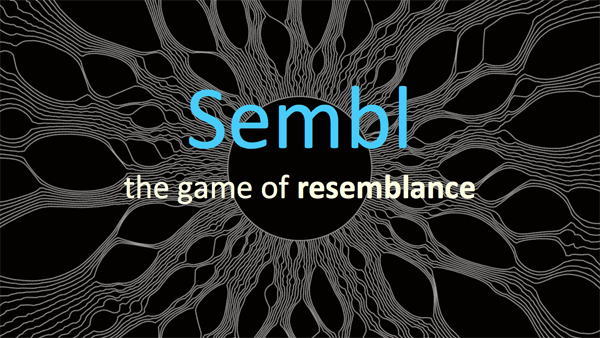

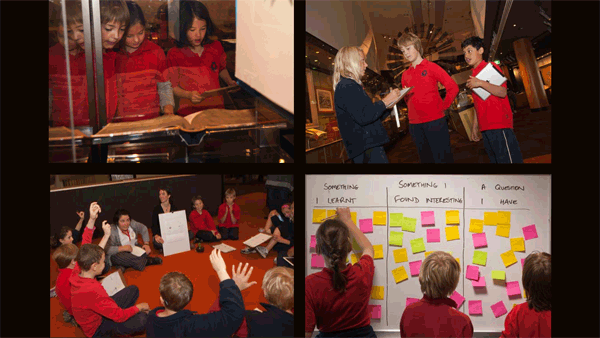

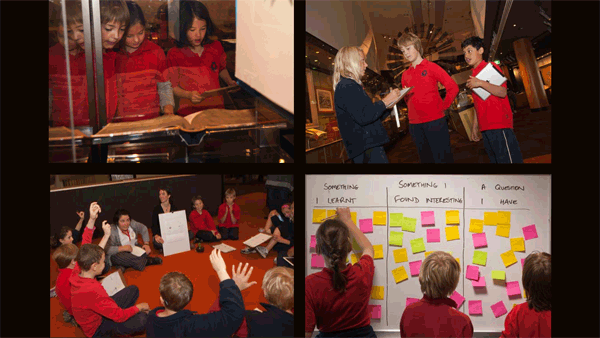

Over the last year and a bit we’ve gathered feedback from children and adults about their experience of playing the game.

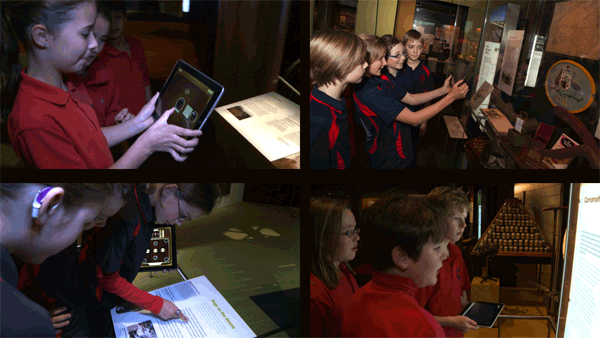

In our first tests, we used a paper prototype; these kids used iPads to take photographs, but the board was paper, and they drew and wrote their moves on paper. Between rounds we had an analogue voting process to determine which team’s content made it onto the board. After the game, we prompted them to tell us a few things about their experience.

Several kids homed in on the principle of resemblance.

Others emphasised the social side of the game.

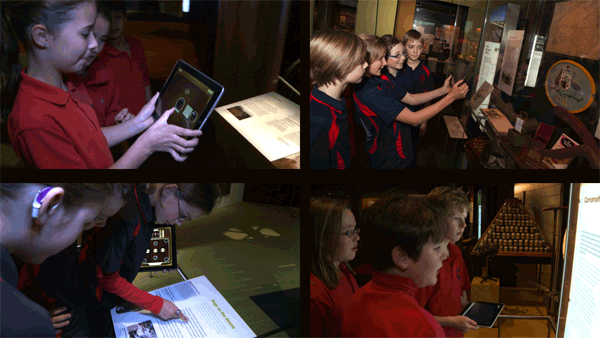

Once we had a digital prototype, we invited the same group back. Again, after the game, we asked them for feedback. The next slide shows some of their responses to the question: What interested you about the game?

Again, there was general interest in resemblance. But the kids are now also talking about being keen to explore the Museum, how the game used the exhibits, and democratic social curation.

I find that fascinating. You might imagine that looking at a museum through a tablet computer would detract from the authenticity of the visiting experience. But for these kids, it seems like it actually draws them in.

Education

We also interviewed the teacher of those kids; she’s convinced of the value of the game for education.

(Here’s a longer extract of the interview.)

Play

Sembl provides a new way to connect to cultural heritage. It’s about play, which is not just for kids. It’s actually a powerful mode of thought, that we lose touch with as we grow up.

As a smart friend of mine says, we all need to recognise ourselves as a maker of meanings and engage in imaginative play. In this next clip, you’ll see a boy whose first language is not English, and historian Peter Stanley, both moving their bodies and struggling with words as they play.

The game gives visitors permission to let their minds wander, to make new kinds of connections, to think differently.

For the host institution, The Museum Game involves a kind of radical trust, and open authority – recognition that knowledge and understanding is not all about curatorial interpretation, that it also comes from visitors thinking and imagining and sharing ideas with each other. Which remains rare in museums, despite the fact that it makes the experience more compelling for visitors.

Dialogue

Another way of saying this is that the Game provides a structure and impetus for dialogue, between the museum and visitors, between visitors and things, among visitors and between things. And this is not dialogue in the sense of an everyday conversation. It’s deeper than that. It’s a mutual experience of looking both ways, simultaneously.

My notion of dialogue comes from the Brazilian educator, Paulo Freire, and his sense of teachers and students as mutually co-intent on creating knowledge.

Quantum physicist David Bohm was also a strong advocate for dialogue.

Each of these notions of dialogue is premised on an understanding of consciousness and how thoughts shape reality. For Bohm, dialogue means holding several points of view in active suspension. He regarded this kind of dialogue as critical in order to investigate the crises facing society. He saw it as a way to liberate creativity to find solutions.

Game-based social learning

So the concept of Sembl, in its deepest sense, is social learning – game-based social learning. In its first instantiation, it is game-based social learning in a museum and – if things turn out as I hope they will – from next year it will be playable at any other exhibiting venue that has the infrastructure and the will to host games – galleries, libraries, botanic gardens, zoos and so on.

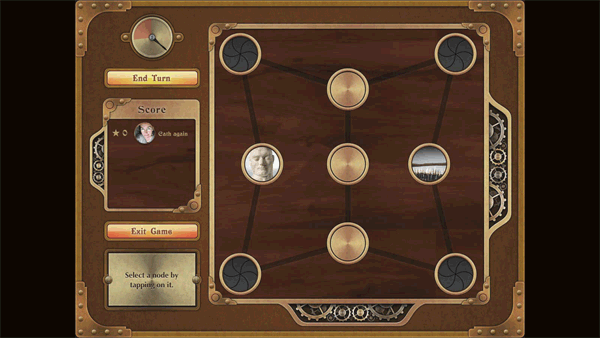

But The Museum Game is just one form of Sembl. The Museum Game is played in real time, on site, and players take photos of physical objects to create nodes on the board.

The next step is to make a web-based form, that you could play at your own pace, and from your own place. Then, Sembl becomes a game-based social learning network, which amplifies the personal value of the game – it becomes social networking with cognitive benefits.

Personal value aside, it’s the bigger picture – of humans as a community – that I most want to explore: Sembl as an engine of networked ideas, or linked data. First, though, a brief diversion to the genealogy of the game.

Genealogy

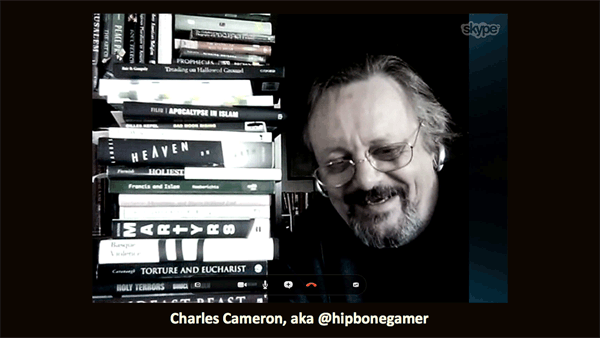

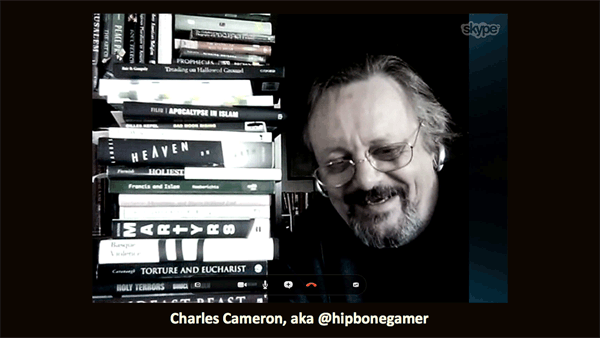

I didn’t invent it! The progenitor for Sembl is a vagabond monk called Charles Cameron.

I’ve never met Charles in person but we’ve spoken a lot over the internet, which is how I took this picture. For 15+ years, Charles has been playing what until recently he called Hipbone Games – because the hipbone’s connected to the legbone. He has always played with a static image of a board, through discussion among players, either face-to-face or online.

And Charles crafts whole symphonies of resemblance about war and religion, art and science.

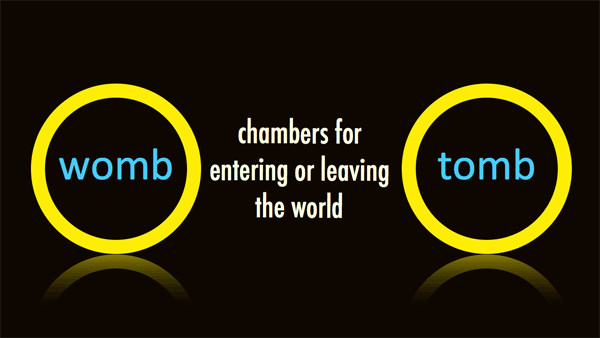

Here’s a classic simple move he made, linking the word-concepts ‘womb’ and ‘tomb’. Charles didn’t invent the game either. Well, not really.

He got the idea from a novel Herman Hesse wrote in the 1940s, called The Glass Bead Game, which as you can see, has a fairly grand vision for the game, to create a kind of music from the entire intellectual content of the universe.

I first encountered Hipbone Games about eight years ago and straight away imagined a digital form, where you could see the network of linked nodes assembling as you play. Ever since then, I’ve been waiting for it to come out in digital… Well, I got tired of waiting, so at some point I adopted it as a personal mission.

Kudos to the National Museum of Australia for building the first digital version. The Museum Game is a simple version of what Sembl can be, but it has potential to grow – and actually, it’s already a little more evolved than it appears in the video at the beginning.

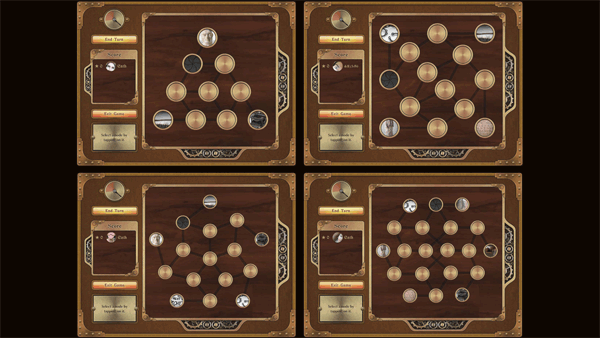

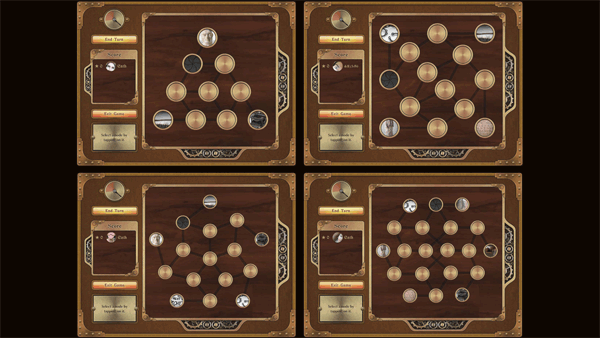

For example, this is the board you saw in the video. We use that one for younger players. But we have other boards, for groups of three teams, for older groups of four teams, for five teams and six.

And in the true spirit of the Glass Bead Game, there’s also talk of hosting tournaments at the Museum.

Toward a game-based social learning network

But it’s at the point of networking the gameplay and the game content that Sembl will really ‘level up’ and rock the world. Once the games are on the web, and the field of playable content is already digital, good things can happen:

- We can aggregate game-generated data and build an interface to the ever-evolving web of resemblance. So it’s not just the thought-riffing in your own game you can enjoy, but the whole generative symphony.

- We can preserve links to the objects’ context in online collections, improving their discoverability – and our knowledge and understanding.

- And – if we harvest the associations to display on the museum’s or other sites – we can forge new browseways within and between collections.

In short, the game becomes an engine of rich, useful data about collection material, and through that the world.

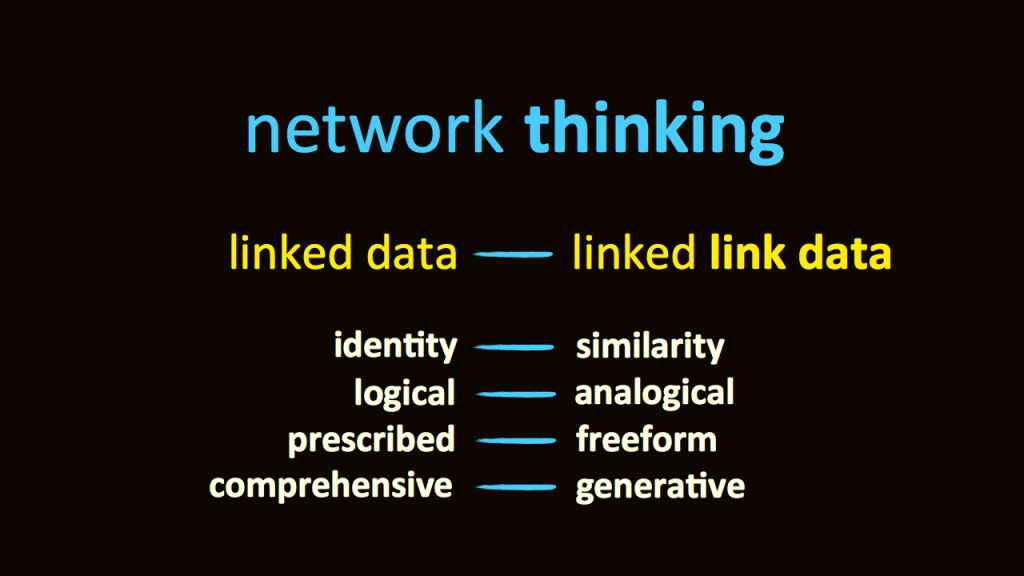

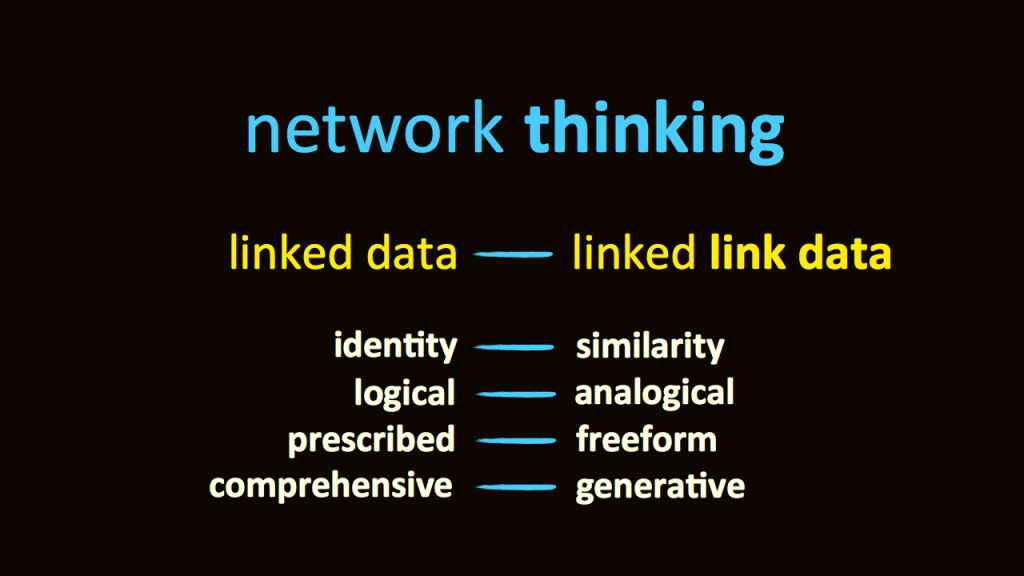

A web-based form of Sembl can generate linked data with a difference. It’s linked link data, and quite different to normal linked data.

- Instead of connections based on what a thing is – sculpture, or wooden, or red – Sembl generates connections based on a mutual resemblance between two things. Which, amazingly enough, is a great way of gaining a sense of what each thing is. And if your interest is to enable joyful journeying through cultural ideas, or serendipitous discovery, this approach just wins…

- Instead of compiling logical links, Sembl cultivates the analogical.

- Instead of building and deploying a structured, consistent set of relationships, Sembl revels in personal, imprecise, one-of-a-kind, free association, however crazy.

- Instead of attempting to create a comprehensive and stable map of language and culture, Sembl links are perpetually generative, celebrating the organic, dynamic quirks of cognitive and natural processes.

But the most important way that Sembl is distinct from other systems of network links is that those who generate the links learn network thinking. Which is a critical faculty in this complex time between times, as many smart people will tell you.

Marshall McLuhan foresaw this shift 50 years ago. Classification is for simple, neat systems. Networks are complex and messy; they demand new forms of literacy. But we have not yet adapted as we need to.

We’re still largely stuck in the Enlightenment thinking that began 400 years ago to institute the binary order of things. But notice what preceded 17th-century ways of knowing. According to Foucault, the ‘primary form of knowledge’ was … resemblance.

Poets have always known the virtues of analogy as a path to the truth.

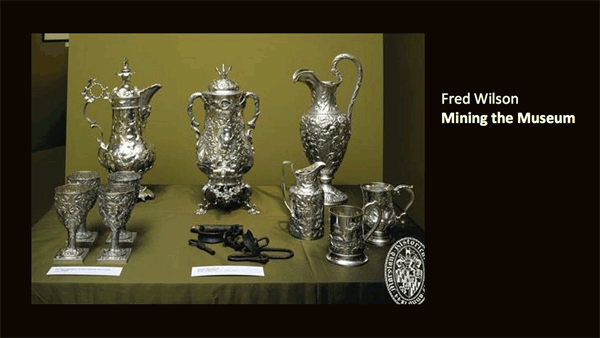

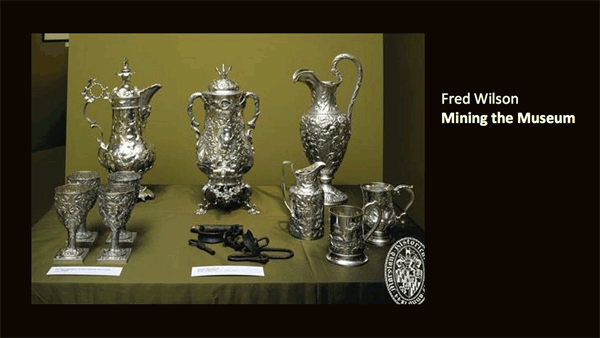

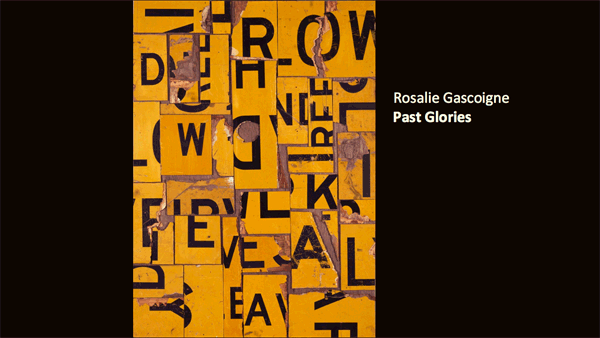

And my favourite visual artists work in this way, creating in-between spaces for us to explore and discover.

As part of an installation at the Maryland Historical Society, African-American artist Fred Wilson placed a set of slave shackles into a cabinet with fine silverware and called it ‘Metalwork’.

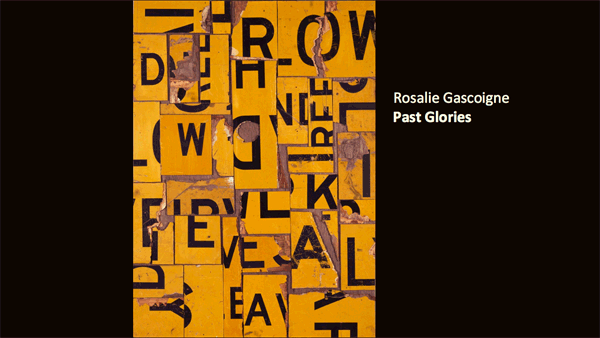

And more subtly, this work is by New Zealand-born artist Rosalie Gascoigne, who lived for a long time in Canberra, where I’m from – so I had to include her… She took discarded signs, disassembled and reassembled them, converting text to textures into which we can read our own messages.

I like the way these artists work; I like how their works induce me to think.

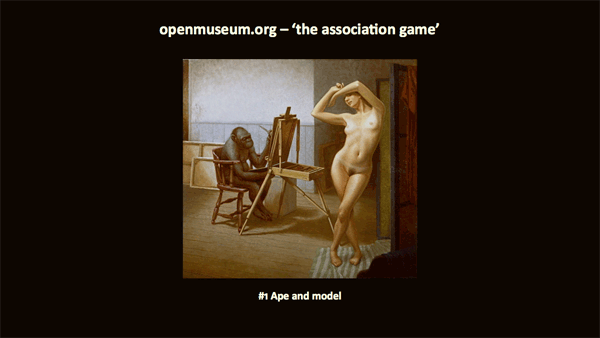

I keep an eye out for opportunities to participate in associative thinking. Last year The Open Museum – a user-generated exhibit site – hosted several rounds of a game where one person would post an initial work, such as this one…

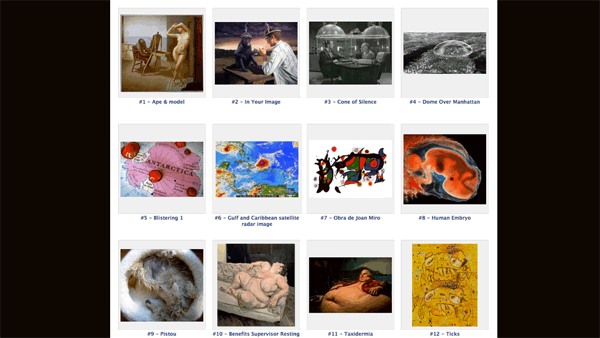

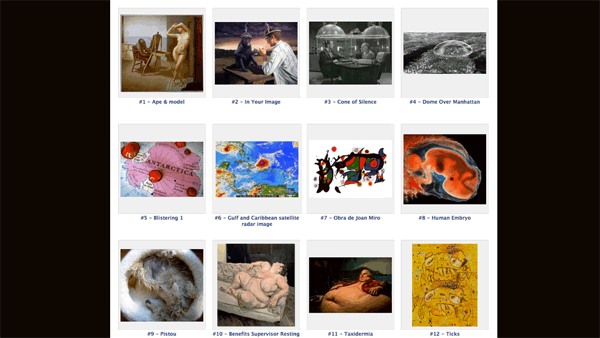

and then anyone else could come along and a post a visually similar work. After a few days the most up-voted work would win the place as the number 2 image, and so on. You can see here how this game progressed in the first 12 moves.

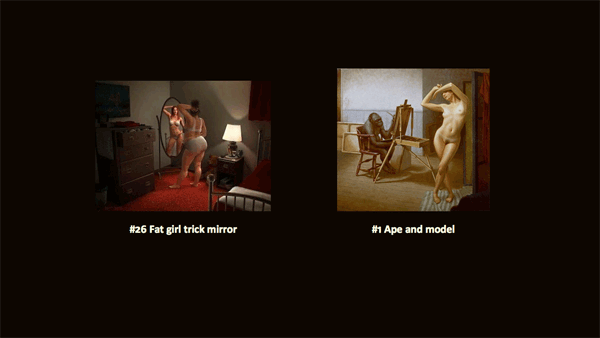

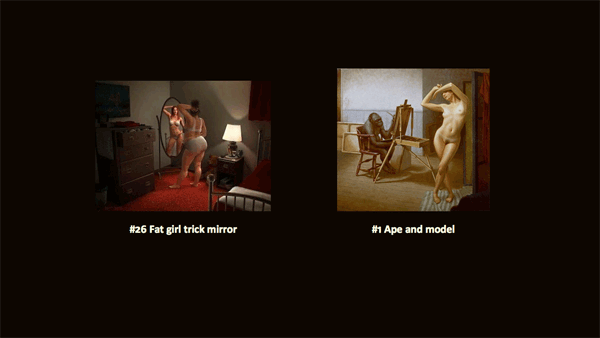

It continued until after 26 moves, it looped back to the original work.

Brilliant. I love how there’s no right answer, and that it encourages wide and wild associations – from a satellite image to a Miro, to a photo of a human embryo.

Polyphonic thinking

Sembl promotes dialogic, non-linear thinking, and new forms of coherence.

It’s distinct from deliberative thinking, which is rational and causal and logical and linear.

It’s another kind of thinking, which might be informed by rational thought, but its purpose is not singular.

You might say its purpose is to create – and cohabit – a state of grace, from which ideas simply emerge.

If playing Sembl gives us practice in polyphonic thinking, if it helps cultivate connectivity and our capacity to find solutions to local and global problems, it is good value. As Charles says, every move is a creative leap.

If you’re interested in working with us to supply content, develop strategy or raise capital, we’re keen to talk.

And I can’t tell you how much I’m anticipating being able to invite everyone to play.

*****

NDF delegates were a truly lovely audience. Having spoken with lots of people about Sembl in the past week – and now that I have a bit of distance from this presentation – I can already see some ways in which I could express Sembl ideas in more pithy, accessible ways. In fact, I plan to rewrite the home page of this site.

In the mean time, know that I would absolutely more-than-welcome further comments, ideas, questions or – of course – resonances with your own context. And if you want to help shape Sembl, you could tell me: in what way are these ideas useful to you, personally and/or professionally? (Or to put this another way: how might you use a tool for network thinking?)