Documenting the process of imagining and bringing-into-being…

A game for 12

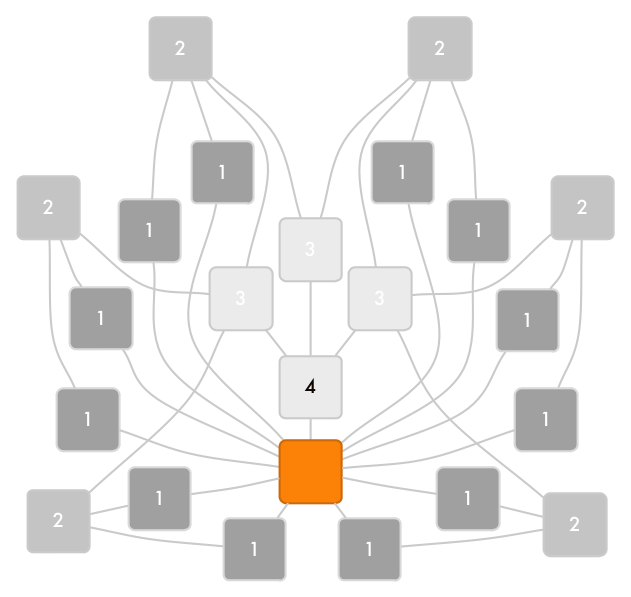

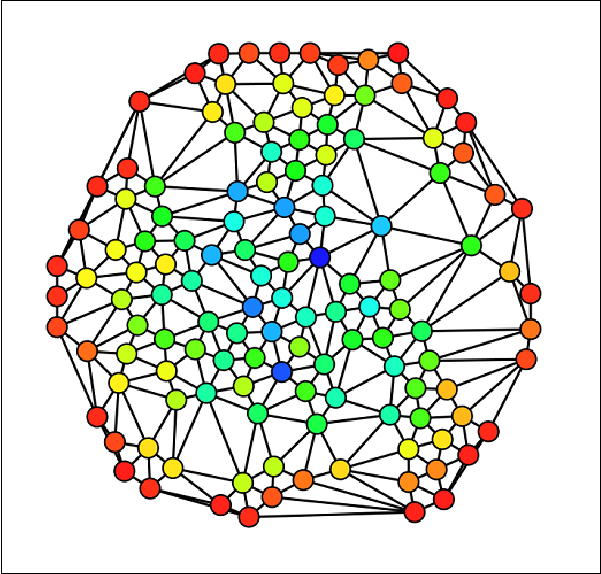

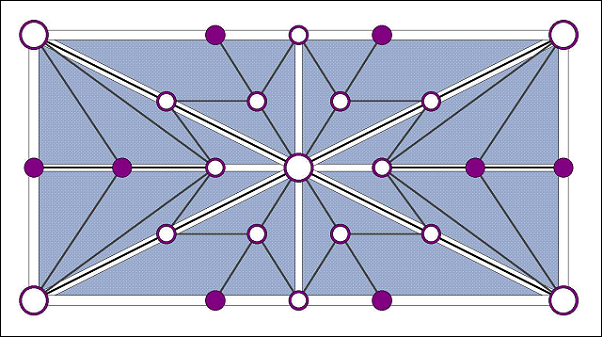

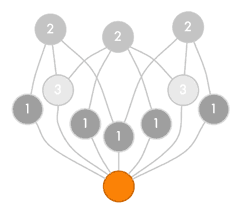

/0 Comments/in Design & development /by CathThis post falls into the category of should-have-blogged-earlier. I designed a board for 12 players.

It’s not one for the faint-hearted. This game has four rounds rather than the usual three, and rating all the sembls would be a four-part marathon – note that in Round 1 you only fill one node, and you never rate the sembls you create:

(Round 1: 11 nodes x 1 connection =) 11 +

(Round 2: 11 players x 6 nodes x 2 connections =) 132 +

(Round 3: 11 players x 3 nodes x 3 connections =) 99 +

(Round 4: 11 players x 1 node x 4 connections =) 44 =

286 sembls to rate

Wow, in total, each game played with this board could generate 12 x (1 + 12 + 9 + 4) = 312 sembls created – 26 for each player.

So now this is the full suite of boards – including a double-quotes form, which could be non-competitive.

On access and use –> cultural material and Sembl

/0 Comments/in Action & reflection, Design & development, Education /by CathA sample of images already in the Sembl system, and some notes on openness, of both cultural heritage material and of Sembl.

In selecting seed material for Sembl, I look in collections that are:

- openly licensed and

- available to download in high-resolution

with a preference for those that also provide:

- a persistent identifier – to link back from Sembl to the source image, and

- plenty of context – date, place, a description and notes on its significance

I choose images that appeal to me but I also seek out material that matches up with keywords – of people, places, events and concepts – extracted from the Australian Curriculum for History and Geography.

So far there are about 800 images in Sembl. Collections I have tapped are:

- State Library of Victoria (125) – photographs of colonial Victoria, product labels and other illustrations collected as part of the copyrighting process

- Getty Institute open content program (142) – objects, paintings, drawings and sculptures, photographs, botanical illustrations, Greek and Roman material

- National Gallery of Denmark (17) – mostly paintings

- Rijksmuseum (105) – artworks, photographs, objects, a 1635 map showing the edge of Australia, diverse other material

- Walters Art Museum via Stanford University (26) – illustrations from medieval manuscripts

- Wellcome Library, London (159) – World War I photographs, extraordinary illustrations and paintings on health-related topics, John Thomson photographs of 19th-century China, amazing maps, lithographs and engravings

- Wikimedia (3) – two Arcimboldo paintings and Rodin’s The Thinker

- Te Papa Tongarewa Collections Online (52) – World War I photographs, landscape photography and art, some Europen art

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art (119) – Asian art and objects, portraits

No doubt, there is plenty more material available that could be in Sembl. Here are some that I have my eye on:

- material from the Biodiversity Heritage Library – eg Ernst Haeckel illustrations of microscopic organisms – as per the header of this blog

- Paul Gervais’ 1844 Atlas of Zoology

- much, much more from Wikimedia

- more from Te Papa Tongarewa – the number of available images grows steadily

- the Library of Congress

As soon as the games themselves are available (and that will be soon!) the process of selecting material to include in games will also be open. Game hosts and players will be able to upload their own material in advance or as part of a game, so you really will be able to play on any subject or problem you care about. (I’m also very interested to hear of collections you would like to play with, so don’t hold back from commenting or contacting me.)

Quite wonderfully, it seems like every week another museum opens the door to a collection to share its treasure. On a dimmer note, many collections are released with a non-commercial re-use licence, which means (I presume) I would have to seek permission to use them in Sembl. Suffice it to say, I will avoid those for now and hope that repositories find a way to become completely permissive as time goes by.

In the same spirit of optimal openness, I want to share the treasure of Sembl. Here are my thoughts on Sembl as an open platform:

- It will always be free to play against random opponents or at the invitation of a game host.

- The system should work on tablets as well as desktop, and meet AA or AAA accessibility requirements.

- Standard rates for game hosting will be flexible for educators and venues who lack the resources to pay them.

- Sembl data – resemblances between collection items – will be available to source repositories to use in their own databases and interfaces.

- Ultimately, my plan is to make Sembl source code available so that the system can be adapted, refined and extended for the benefit of all patrons.

On the felicities of graph-based game-board design: two dazzlers

/0 Comments/in Design & development, Further afield /by Charles[ cross-posted from Zenpundit — completing a post that began with On the felicities of graph-based game-board design: preliminaries ]

.

Having shown you a variety of (node-and-edge) graphs in the previous part of this post —

— I’d now like to turn to the issue of board game design, in particular as it applies to the HipBone and Sembl games with which I’m associated.

Since the basic idea of these games is to see the links between one idea and another, graphs of this kind are the simplest and most elegant boards on which to represent game moves. Accordingly our games boards, from the simplest Hop, skip and a jump board that I’d use to introduce kids to the games —

— via my standard HipBone WaterBird board —

— to the complex and still only part-played Said Symphony board —

— and indeed beyond, to Cath Styles‘ elegant Lotus Board for the Australian Museum Game —

— all our boards are graphs — and any graphs that catch my eye are potential boards, waiting for me to figure out whether they’d actually work in play, or might suggest any new ideas for board design.

I therefore felt very lucky indeed one day this week, when I ran across two striking, indeed dazzling graphs in quick succession.

Artist Ellen van der Molen makes a speciality of mandalas — those circular and often highly symmetrical images, common in Hindu and Tibetan art, that Carl Jung viewed as “the psychological expression of the totality of the self” — but it was this particular one featuring “graph” imagery, which she titles Lotus Grid, that dazzled me:

There’s an interesting and delicately balanced asymmetry to the graph in this mandala, and it makes me think of board design in less tightly controlled, more flowing ways.

More of Ellen’s work can be found here [link]: my “next favorite” of her works features simple, elegant calligraphy in an unknown language — here.

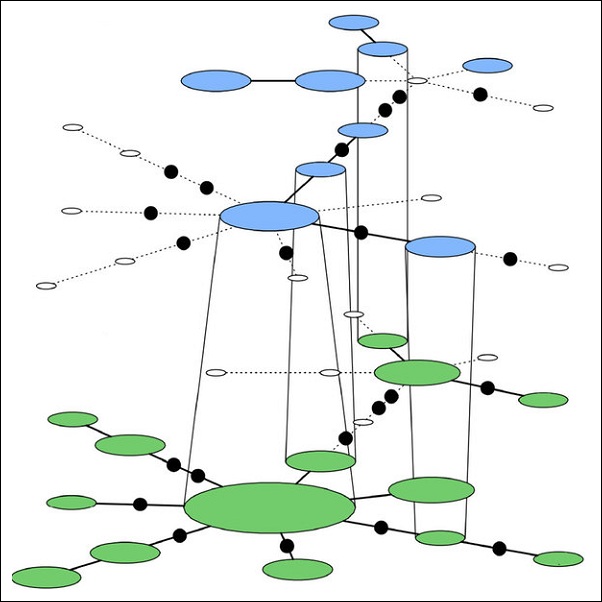

So that’s from the art side of the house — while on the science side I ran across this graph at about the same time.

I have snagged it from an academic paper by Andrew D. Foote et al, titled Ancient DNA reveals that bowhead whale lineages survived Late Pleistocene climate change and habitat shifts, in Nature Communications 4, Article number: 1677, doi:10.1038/ncomms2714, Figure 3: Survival of bowhead whale lineages during the Pleistocene–Holocene transition. I have removed only the words Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, which were relevant in the graph’s scientific context, but would only have been confusing in terms of my game design discussion here:

And that, my friends, is stunning for a whole other set of reasons — it suggests what a three-dimensional HipBone or Sembl game board might be like, and frankly it leaves me fumbling for ideas.

What might the upper (blue) and lower (green) levels signifiy, in terms of play? What affordances would a 3-D board offer, that one of our simple 2-boards can’t? Where can I take my thinking about graphical board design, once I have seen this, and allowed it to sink into my generative unconscious?

I don’t know the answers, of course. I don’t know what either of these two images will do to my own thought processes — but they’re like two pebbles dropped fortuitiously and almost simultaneously into my mirroring pool, and their ripples are surely spreading.

My grateful thanks to both Ellen van der Molen and Andrew D. Foote and his co-authors.

One idea leaps to another, and so the games proceed.

On the felicities of graph-based game-board design: preliminaries

/0 Comments/in Design & development, Further afield /by Charles[ cross-posted from Zenpundit — on graph theory, and the background and history of HipBone / Sembl gameboards ]

.

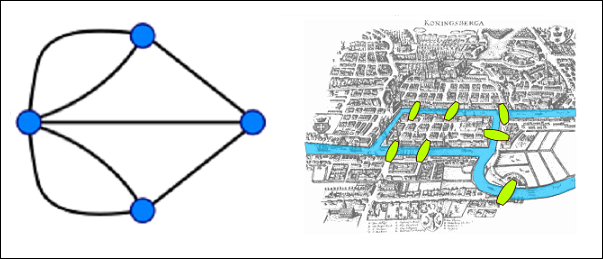

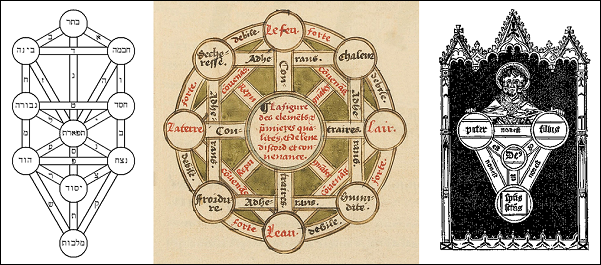

First off, a graph — at least the way I’m using it here — is a diagram of linkages. The items linked, which may be people, places, phones, ideas, quantities, whatever, are represented by dots or circles, known as nodes, and the links between them by lines, known as edges.

Here’s a simple graph diagram with four nodes and seven edges:

That diagram represents — elegantly, with topological accuracy — the seven bridges connecting the banks and islands of the city of Königsberg — which gavs rise to a famous math problem, which in turn gave rise to that branch of mathematics we now know as Graph Theory.

Graphs are thus pictures of networks, and networks are the non-linear, feedback-capable basis for an astonishing variety of interesting things such as the internet and your and my brains…

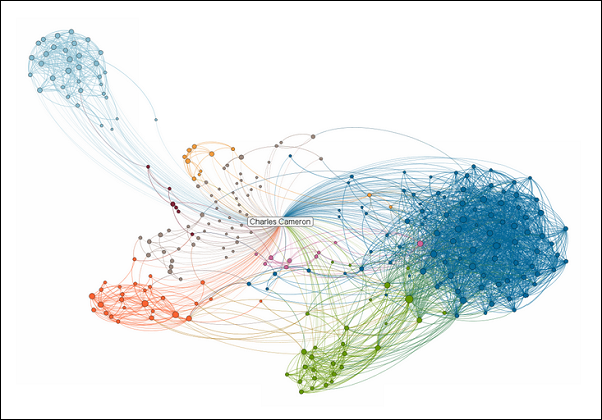

And they can get pretty complex. I’m a simple soul, and not a great network maven — but here’s what my network in LinkedIn looks like as of today. It too is a graph, although it reminds me of broccoli, or of a fish…

Hey, that’s a pretty small network — and graph — compared with, say, a graph of all the neurons in a single brain, all the brains on the world’s computer networks, or all the neurons in all the brains on all the networks…

Graphs with concepts at the nodes and conceptual links along the edges have been used for centuries to convey mystical states, propositions in theology, and concepts in the natural sciences:

Left, the Sephirotic Tree in Kabbalah; middle, the four elements in Oronce Fine; right, the Christian Trinity

So you won’t be too surprised to learn that my variants on the Glass Bead Game of Hermann Hesse, which are designed to build what he termed the “hundred-gated cathedral of Mind” by analogically connecting the great thoughts of human-kind across all the arts and scences, use graphs (in this sense) as their boards…

Here, for instance, is one possible board design, derived from the inner vaulting of an English cathedral roof:

Okay, past is prelude.

In the second part of this post I’ll show you a series of boards actually used in HipBone / Sembl play, and then two dazzling works — one a work of art, the other a work of science — that leapt out at my in the course of my browsing a morning or two ago…

18 years, and what a difference!

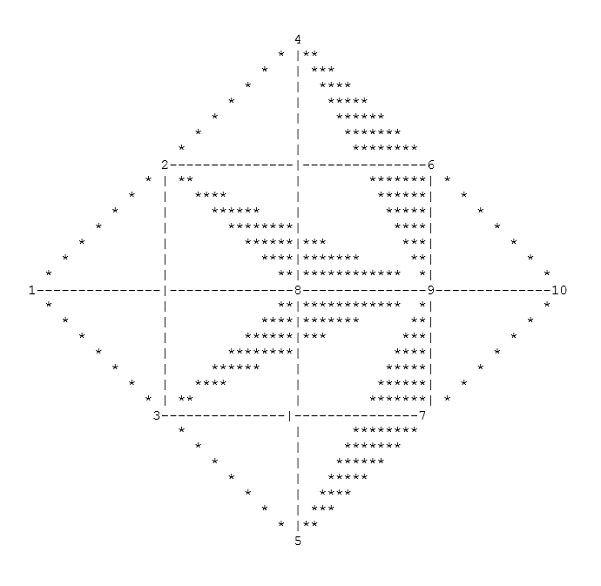

/0 Comments/in Design & development, Further afield /by CharlesEighteen years ago, in 1996, we used to play HipBone Games by email (“PBEM”). The boards were literally typed out in ASCII characters — to give you the idea, here’s the WaterBird Board as we played on it back then…

Eighteen years have passed, and the latest board in the genre, designed for the Museum Game, looks like this:

Simply beautiful, Cath!

We’ve come a long way… and I’m eager to see where we’ll be heading next..

Cultivating conceptual propinquity

/0 Comments/in Design & development /by CathDialogic thinking doesn’t only mean taking into account two different perspectives; it also means recognising the common ground between entities – what it is that makes them one. This post is a note about game mechanics to cultivate conceptual propinquity.

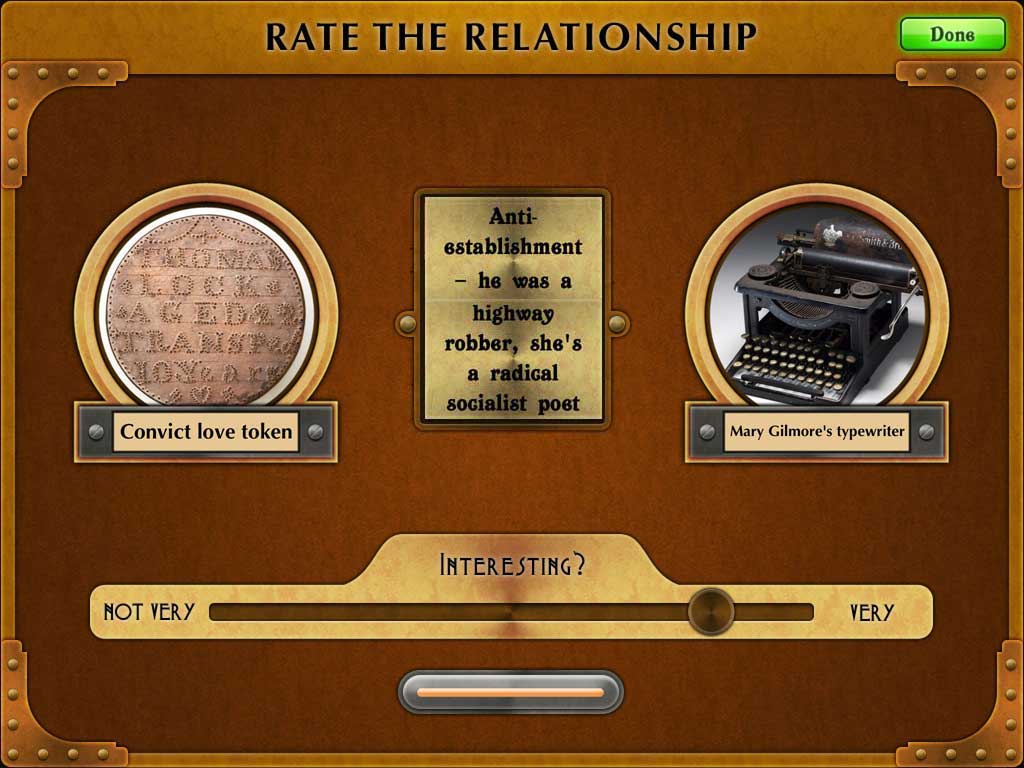

In Sembl games, players form associations between pairs of objects or concepts. Evaluating others’ moves according to a sliding scale of interestingness provides for a great gamey dynamic. It’s fun, and about as open and social a contest as you could imagine.

More importantly, the mission to associate, and the challenge to be interesting – both invoke and honour dialogical play, sparking all manner of logical and analogical associations between nodes. In aggregate, those associations form a new big picture of the networks we inhabit, which in turn can help us to communicate better via machines.

But to operate optimally, Sembl needs an additional filter.

Sembl’s true power lies in its capacity to surface similitude – links that are mutually applicable, or bi-directional. Such links do not make a comparison; they unite.

Having now observed dozens of games played at the Museum, I notice that players often deviate from my purist approach, and create links in the form of this-whereas-that, associating the pair by way of an opposition or a third element. Such moves can be highly humorous and thereby interesting, but asymmetrical links do not serve the purpose of drawing disparate objects and concepts together, so their interest is more fleeting. Asymmetrical linked data is also, as I have ranted earlier, subjective, sometimes objectionable – even authoritarian.

The act of perceiving a resemblance between things conceptually distant elicits understanding of important hidden-in-plain-sight patterns. A sense of connectedness – or the overview effect – is insightful and can fill us with wonder at the beauty and fragility of the Earth. Such a perspective can also yield understanding of the structures that divide us.

Beyond its liberatingly loose notion of interestingness, Sembl needs to surface higher-value, propinquitous links – those with a centripetal force – those that specify the nature of a similitude. I’m therefore thinking that… Players should be able to mark down links that don’t work both ways.

Torus and lotus

/1 Comment/in Design & development /by CathLast year I posted about the gameboard designs we’re using in the Museum form of Sembl.

On those boards, each team starts with their own seed node – so on the hex board there are a whopping six nodes not created by players. I wanted less space to be taken up on the board by the seed content, to leave more space for the player-generated content. Conceptually and logistically, it also simplifies entry to the game if everyone focuses at first on a single node.

So I made two new boards, for four and six teams, where each team begins from the same node. In Round 1, the game expands, in Round 2 it contracts, and then in Round 3 there’s only one or two nodes left to claim. Because of this opening out and then closing in, I call these the Torus boards.

Having built a fancy Graffle-gameboard converter, the trusty lads over at Secret Lab were able to easily provide new gameboards for us to play in the iPad game. The two Torus boards fast became our favourites. Here’s what the Torus 4 looks like in The Museum Game:

But last night I realised I’m still disappointed in those designs, because they’re not really, truly, toroidal – because you don’t actually end up where you started. I realised that the Round 3 node/s should link back to the seed item, like this:

Because how could I not, I call these latest boards the Lotus series and I can’t wait to put them through the Graffle gameboard-o-matic. I sure hope it can handle curves and crossovers.

[edited 15 July to add the following…]

Turns out crossovers are fine but curves demand engineering we can’t prioritise. So… here again with straight lines:

Sembl for GLAMs

/0 Comments/in Design & development /by CathOver the last couple of months I’ve been asking myself: how can Sembl help galleries, libraries, archives and museums (GLAMs) do what they do, better? Actually, I’ve been asking myself the same question in relation to educators, but that’s for a later, longer post. For now, I’m sharing some of my thinking and action in relation to the GLAM sector.

Sembl needs GLAMs.

In Sembl games, players are challenged to to find interesting ways in which things resemble each other. To perform these analogical feats, players need access to a generous array of things or entities – let’s call them nodes. Nodes are comprised of images of items in the world’s cultural heritage collections.

And GLAMs need Sembl.

GLAMs are in the business of collections interpretation and education. They need their collections to be accessed. (Which is why supporters of OpenGLAM are coalescing into a powerful force – hooray!) But beyond ‘accessing’ their collections, GLAMs need people to contemplate, wonder about, and respond to them. Sembl induces people to do exactly that. By contributing collection material to it, GLAMs can tap into a new – and wonderful – platform for social learning.

Because I wasn’t sure whether GLAMs would see it that way, I set up a short survey, inviting staff of GLAMs to estimate the likelihood of their institution becoming involved with Sembl as a contributor of content, and as a host of online and onsite games. This is not large-scale, long-range or in-depth market research; I did all my respondant-soliciting via Twitter. But the responses – mostly from people in large institutions in Australia and New Zealand – indicate that there is indeed a market for Sembl among GLAMs. Here are some highlights:

- 96% of institutions either would or might be likely to contribute content

- 72% would be keen to host games online if the return on their investment seemed good

- 84% might want to host real-time tournaments onsite

Thank you, dear respondents! You have given Sembl a small but essential boost.

The Story of Sembl, I: Herman Hesse’s Glass Bead Game

/0 Comments/in Design & development, Further afield /by Charles[ first post in a series on the inspirations and developments that led to Sembl, and the aspirations that flow from them ]

.

Music for a Glass Bead Game, Arturo Delmoni & Nathaniel Rosen — a musical tribute to Hermann Hesse’s Game from John Marks Records

While other novelists on the whole explored the “real world” around them, the outside world, the world of other people and things, Hermann Hesse was concerned with the “inner” world – the world of hopes, dreams, distress, anguish, rage and insight. With his 1927 novel Steppenwolf, he introduced us to the “dark side” of ourselves, our “shadow” to use Jung’s term, long before Star Wars, longer before the Sith Lord Cheney committed the United States to work “sort of the dark side, if you will … to spend time in the shadows in the intelligence world.” And if Steppenwolf showed us our shadow, in his earlier novel Siddhartha (1922) he had already shown us the light – in a deliciously sensual revisioning of the young Buddha‘s ascetic purity.

Siddhartha and Steppenwolf between them provided cover for generations of young idealists coming to terms with their own dreams and nightmares, but it was in his final great novel Das Glasperlenspiel (1943), known in English as The Glass Bead Game or Magister Ludi, which won him the Nobel Prize in Literature while confusing and losing many of his admirers — and inspiring beyond measure those who stayed with him.

Hesse’s grand vision was of a game played by the members of a scholarly caste – monastic Brahmins of a secular, post European world – whose purpose, pleasure and play it was to bring all human culture into one architecture, one music, woven of similarities, parallelisms, patterns, archetypes.

As an architecture of insights, Hesse spoke of this great game of his as “harmoniously building the hundred-gated cathedral of Mind.” In musical terms, he described the game as a virtual music in which “ideas” rather than “melodies” would be harmonized or held in counterpoint:

All the insights, noble thoughts, and works of art that the human race has produced in its creative eras, all that subsequent periods of scholarly study have reduced to concepts and converted into intellectual values the Glass Bead Game player plays like the organist on an organ. And this organ has attained an almost unimaginable perfection; its manuals and pedals range over the entire intellectual cosmos; its stops are almost beyond number.

And the game’s ultimate destination – besides the creation of an overarching synthesis uniting sciences and arts, great leaps of discovery and profound flights of imagination?

Every transition from major to minor in a sonata, every transformation of a myth or a religious cult, every classical or artistic formulation was, I realized in that flashing moment, if seen with a truly meditative mind, nothing but a direct route into the interior of the cosmic mystery, where in the alternation between inhaling and exhaling, between heaven and earth, between Yin and Yang, holiness is forever being created.

The ultimate aim is contemplative simplicity, meditation, a renewed sense of the sacred.

❧

It was not the characters in the novel, nor its plot, that won Hesse the Nobel Prize: there is hardly a female character in the entire book, the males are largely cardboard imitations of people, and the plot such as it is might have made a fine twenty page novella – no need there for a 550-page masterpiece.

No, it is the game itself that holds the imagination, as the Himalayas might hold the attention of one who had lived a lifetime in the lowlands. And catch hold the imaginations of brilliant minds it has.

Hesse’s old friend and rival Thomas Mann inscribed a presentation copy of his novel Doctor Faustus with the words: “To Hermann Hesse, this glass bead game with black beads.”

Christopher Alexander, the progenitor of pattern languages, distilled the essence of his own thinking in his “Bead Game Conjecture”:

That it is possible to invent a unifying concept of structure within which all the various concepts of structure now current in different fields of art and science, can be seen from a single point of view. This conjecture is not new. In one form or another people have been wondering about it, as long as they have been wondering about structure itself; but in our world, confused and fragmented by specialisation, the conjecture takes on special significance. If our grasp of the world is to remain coherent, we need a bead game; and it is therefore vital for us to ask ourselves whether or not a bead game can be invented.

Manfred Eigen, Nobel laureate in Chemistry, wrote of his book on molecular biology with Ruth Winkler-Oswatitsch, Laws of the Game:

We hope to translate Hermann Hesse’s symbol of the glass bead game back into reality.

John Holland, father of genetic algorithms, told an interviewer:

I’ve been working toward it all my life, this Das Glasperlenspiel. It was a very scholarly game, starting with an abacus, where people set up musical themes, then do variations on it, like a fugue. Then they’d expand it to where it could include other artistic forms, and eventually cultural symbols. It became a very sophisticated game for setting up themes, almost as a poet would, and building variations as a composer. It was a way of symbolizing music and of building broad insights into the world.

If I could get at all close to producing something like the glass bead game I can’t think of anything that would delight me more.

❧

Mid-way between architecture and music, forming an arch between the arts and sciences, Hesse’s imaginative game has been construed on many levels and in many ways, serving the needs of molecular biology, artificial intelligence, architecture and more. But what of its nature as a game to be played?

From my point of view as a game designer, Hesse’s game is both an artwork – to be played as Bach or the blues are played – and a game – to be played as soccer or chess are played.

And what a game!