A dialogic order of knowledge

This post is a provocation, triggered by Mike Bergman‘s clear and interesting talk on the semantic web in use. It follows some earlier, fuzzier thinking of my own on Sembl and linked data. I now understand where Sembl fits in relation to the semantic web. The answer is that it doesn’t, not really, because Sembl triples are quintessentially different to RDF triples. Different and, I contend, better.

Here’s the problem – just reiterating here, for people who are unfamiliar with ‘the semantic web’. We made a beautiful web, huge and full of knowledge, but it’s too big for humans to use well. We need machines to process the bulk data so we can extract the most relevant gems of knowledge. But for machines to understand the whole web of human knowledge, they need the parts to be arranged in a more orderly way. Is this thing the same as that? If not, what’s the relationship between the two? Machines fail to articulate the parts, and humans are never sure we’ve got the best part of the big picture.

What we need is an authority file for What Each Entity Is and How It Relates to Other Entities; an agreed way to inform machines of the complex variations and dynamics of human knowledge.

Semantic web proponents have succeeded in creating an agreed process for defining and agreeing on What Each Entity Is. Mike Bergman describes the use of URIs to identify data as the semantic web’s ‘crowning achievement’. But the second part of the challenge – How Each Entity Relates to Others – is critical, and tricky. And the current approach – build and/or mash up and apply ontologies, vocabularies, thesauruses, schemas and taxonomies – feels labour-intensive and ineffective.

The web is about as non-linear and dynamic a system of knowledge as you can get, yet we try to describe it in terms of the sum of its components.

What if we’re going the wrong way in our mission to understand things in relation to other things? What if the basic building block of the semantic web structure, the triple, is sub-optimal? At the very least, it is insufficient. Consider:

This entity

[subject]

↓

has this relationship to

[predicate]

↓

that entity

[object].

Let’s face it: triples are reductive and authoritarian. Always starting with the subject and ending with the object, they seek out and cultivate otherness. Whatever the part in the middle is, the subject gets to co-opt the object into a relationship that is always already from the subject’s perspective. Sometimes the subject’s defined relationship to the object is consensual. And sometimes it’s inappropriate. The thing is, even if you carefully pass all your triples through the complex regulatory system they necessitate, you can never be sure you’ve got the relationships right. And if they are validated at one point in time, they may later need updating.

In short: triples are intended to impose order, but they tend to create conflict.

Triples are not evil. Often the predicate is unifying, a form of equivalence, something along the lines of ‘is the same as’. Too often, according to Mike, who lamented the ‘SameAs’ relationship’s overuse. He also showed us a list of various terms for defining the near-identity of different entities – my personal favourite is ‘somewhatSameAs’:

Evidently there is a reconciliatory bent among the seekers of the semantic web, a force resisting the oppositional stretch of the triple :)

And… therein lies an answer to the problem of imposing order without generating disagreement.

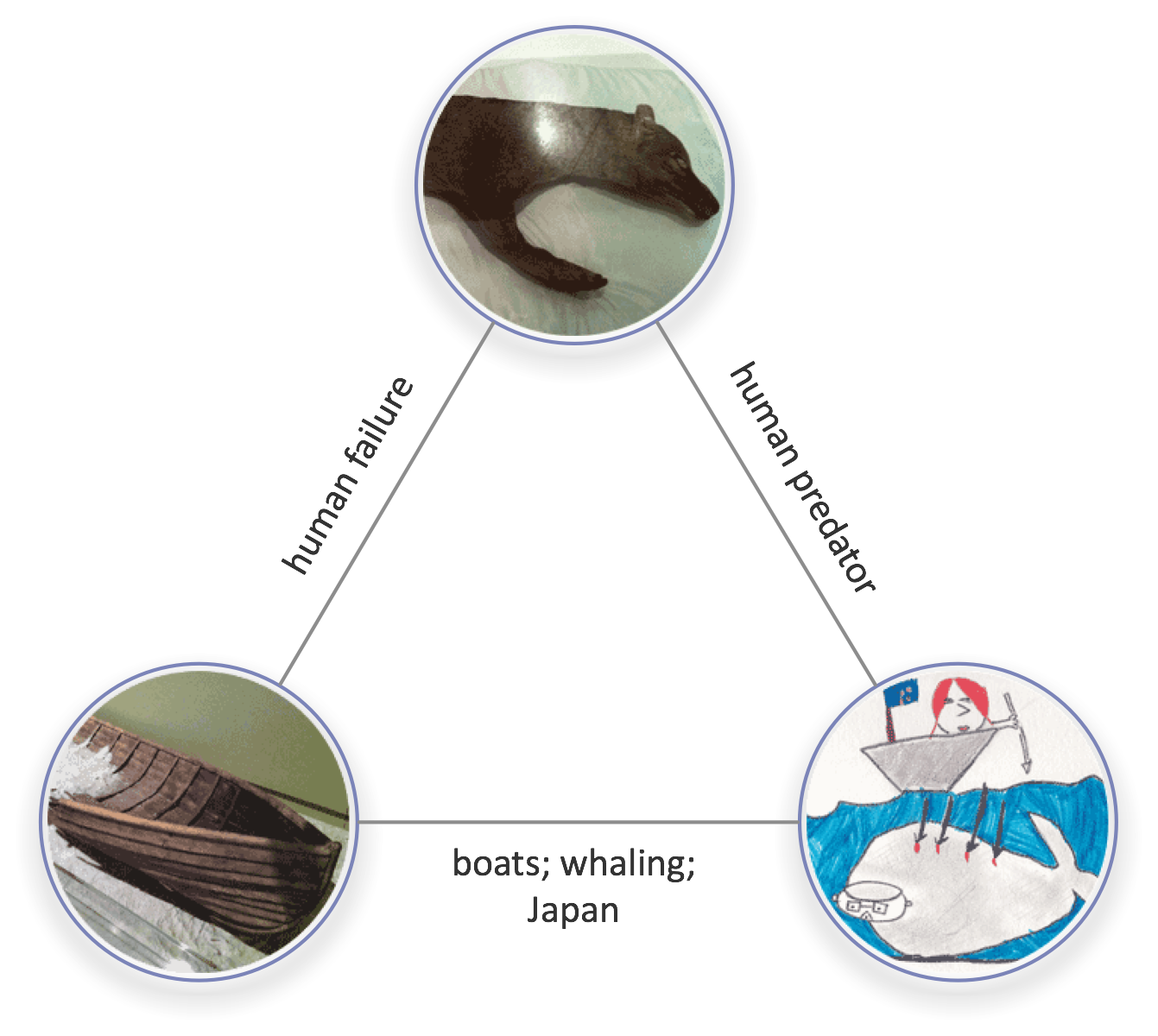

Instead of trying to map the complete tangle of relationships, we could focus on crafting resemblance. We could ditch the one-way triple in favour of a mutual one:

This thing

[subject]

↓

shares this resemblance with

[predicate]

↑

This thing

[subject].

Resemblance is by nature imprecise, but because its perspective is mutual, it is never wrong. The spectrum of resemblance runs from fairly uninteresting (eg a glass and a bowl both have a round rim) to the startling, insightful, poetic. And whether humans like the resemblances or not, every single one will help the machines to understand – whether they are written in ‘proper English’, vernacular, or any other language.

Resemblance is a very human approach to structuring knowledge. It is generative rather than reductive, and it is intrinsically attractive – both conceptually, in the sense of drawing two entities closer together, and emotionally, in the sense that it feels better to seek similarity than to define difference. We are naturally dialled-in to similarities and patterns. And this capacity is extremely useful for seeing how the parts relate to the whole. Which is, I recall, the mission of the semantic web.

Obviously, there will still be difference. In fact, it turns out that to identify sameness is to explore difference. As soon as you find a resemblance between two things, a difference pops up. Intriguingly, difference seems to make more sense, and be more palatable, in the context of resemblance. It’s kind of beautiful.

To create an online version of the Sembl game – a Sembl Web – we will need to use stable URIs or to create them if they don’t exist. By default, I’d like to link Sembl entities to Wikimedia. But can we hack the RDF triple and forget the vocabularies and ontologies?

Freed from having to define and structure all the possible relationships in advance, we could invest energy in exploring the territory of relatedness at our leisure, and begin to work out a pattern language for them. We’d be building a knowledge system based on consensus instead of authority.

Wikipedia changed how we create and access shared knowledge. Sembl could change how we create and access shared knowledge of how it all fits together.

The semantic web is big, in theory. There are over 7 billion RDF triples already, though according to Mike ‘very few’ are put to use. Sembl Web doesn’t yet exist, but when it does, it will constitute a humane generator of mutual triples – triples that:

- are always already in use

- bring joy to the people that create them

- fit the dynamic non-linearity of the web

Sembl is poised to create complex, chaotic flow among disparate parts of the web. And that flow is the point. That’s what converts knowledge into understanding.

…..

Disclaimer: I’m no expert on the semantic web. If I have overlooked something critical in the above, I’d appreciate you letting me know. On the other hand, if you see value in this approach, please let me know where and how. Ie, comments appreciated!